With bird flu cases rising, certain kinds of pet food may be risky for animals – and people

When Jamila Acfalle decided to get her first cat, she had one requirement: It had to be brave.

Acfalle is a dog trainer in a suburb of Portland, Oregon. She works with dogs that have behavior problems that put them at risk of rehoming or euthanasia. She needed a cat who wouldn’t be intimidated by the large, bouncy canines she brings home.

When she met a litter of long-haired Maine Coons in 2021, the smoke gray kitten who walked straight up to her and sat at her feet was the one.

Because her dog’s name is Hero, she named the cat Villain. The cat was friendly and silly but quickly learned to put the dogs in their place. Perhaps because she was already so used to working with dogs, Acfalle trained her to walk on a leash so she could take walks with her fur brothers.

She also wanted to be sure that Villain ate a high quality diet. Like a growing number of pet owners in the US, she liked the idea of giving her pets raw food, which she believes is healthier since it was less processed than dry kibble and perhaps more similar to what animals eat in the wild.

Americans’ interest in raw foods — for pets and humans — has surged, fueled by a growing distrust in highly processed foods and chemical additives.

Infectious disease experts, however, say the trend goes too far, since it abandons tried-and-true safety steps — including heating milk and cooking meats — that kill dangerous viruses and bacteria. In the era of bird flu, they say raw milk and raw pet food are bringing a dangerous virus with pandemic potential too close to people and pets.

On Friday, the US Food and Drug Administration announced it is tracking multiple cases of H5N1 in domestic and wild cats, including cases linked to contaminated pet food. The FDA advised that while dogs can also be infected, their symptoms are usually milder. Cats, however, are at greater risk.

The agency directed pet food manufacturers to consider the risk of bird flu in their required food safety plans, including adding a step to cook animal products like milk, meat or eggs, or adding supply chain controls to ensure that the products they’re using in their food don’t come from infected flocks or herds.

“We encourage consumers to carefully consider the risk of this emerging pathogen before feeding their pets uncooked meat or an uncooked pet food product,” the agency said.

Acfalle said she researched several brands while deciding on Villain’s diet and looked for one she thought was taking extra steps to be safe.

“They’re just frozen little nuggets. And you scoop them out, and they defrost, and you smash it down, and it’s just raw meat, organ and bone. And she had been eating that her whole life” and thriving, Acfalle said.

Until she wasn’t.

Just after Thanksgiving, Villain spent eight days with an illness that confounded their local vets. First, she stopped eating, then she stopped going to the bathroom, and she began to struggle with balance and coordination.

As her condition worsened, Acfalle bought a variety of foods, making a kitty smorgasbord of different smells, trying to entice her to eat. Instead, Villain tried to smash her face into the food.

“And then she was just walking back and forth,” Acfalle said. The pacing went on for hours. “She wouldn’t stay still. She’s just constantly moving, and she’s trying to lay down, but then she wakes up as if something’s trying to get her, and she’s scared.”

The next morning, Villain was barely able to open her eyes. Acfalle rushed her cat to an emergency animal hospital, but it was too late. Villain’s brain had begun to swell, and she died in Acfalle’s arms.

In shock and disbelief that she’d lost her beloved 4-year-old companion, Acfalle took the extraordinary step of sending Villain’s body to Oregon State University for a necropsy, to find out why she died.

The phone call she got next was devastating.

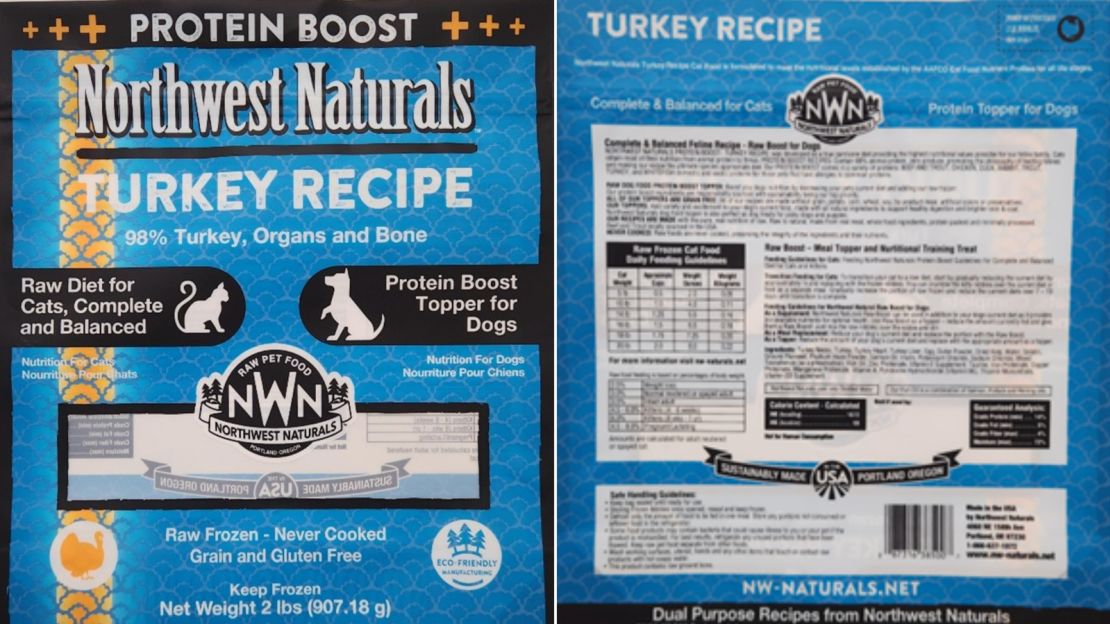

It was H5N1 bird flu, and state officials said it came from a contaminated batch of the Northwest Naturals pet food that Acfalle had fed her own pets and recommended to her clients.

“I really wanted it to come back as a blood pathogen or something that couldn’t have been in my control, but I felt responsible for choosing that for her, for choosing a raw lifestyle for her,” Acfalle said. “I felt responsible.”

Acfalle said she had to take Tamiflu to ensure that Villain had not passed the infection to her. As another precaution against spreading the virus, she wasn’t allowed to have Villain’s ashes after her cremation.

Raw foods bring bird flu closer to pets and people

H5N1 infections are rare in American pets, but they’ve become increasingly common over the past two years as the virus has begun to circulate in a growing variety of animals, including dairy cows and farmed poultry like turkey and chicken.

Cats are particularly vulnerable to the virus. As with chickens, the virus can invade their brains and cause devastating neurologic complications.

Since December 2022, at least 74 pet cats have tested positive for bird flu across the United States, according to data from the US Department of Agriculture. Domestic cats are the third most common detection of H5N1 in non-farm mammals in the US, behind red foxes and mice.

That official tally of infected cats is almost certainly an undercount, too.

“With foodborne disease, we capture a small percentage of them,” said Dr. J. Scott Weese, a veterinarian and professor at Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph in Canada. Weese specializes in the study of zoonotic infections — infections that spread between people and animals.

Weese said cats usually get less vet care than dogs, so they are in clinics a lot less often. When cats get the flu, they can deteriorate very quickly and may not show signs of illness until it’s too late.

To be added to the official count, animals not only have to be seen in a vet’s office, they have to be tested, and those test results have to be reported to the state, which has to confirm them. Pet owners must pay for most of these steps, which can be a further disincentive.

“You might have a cat that’s looking a little bit off in the morning. The owner says ‘yeah, the cat’s not looking that great. Let’s see what happens,’ ” Weese said. “They might be dead overnight. Most people aren’t going to take their animal in for testing afterward.”

Joseph Journell of San Bernardino County, California, said he spent thousands of dollars trying to understand why three of his cats suddenly became gravely ill in November.

Two of his cats, a 4-year-old black and white kitty named Tuxsie and a 14-year-old tabby named Alexander the Great, died.

A third cat, Big Boy, became critically ill. He went blind and lost the ability to walk. Veterinarians at a specialty animal hospital were able to test his urine for bird flu. After weeks of aggressive treatment, including the antiviral drug Tamiflu, he has recovered.

All three of the cats, who lived indoors, drank raw milk from a batch that was later recalled by Raw Farm dairy after it tested positive for the H5N1 virus. Journell said that a fourth cat who did not drink the milk never got sick.

For weeks starting in December, California-based Raw Farm was quarantined and stopped producing and distributing its raw milk. It has since resumed sales after clearing the required tests. The company disputes that its milk made Journell’s cats ill, but he remains convinced.

Journell also drank the Raw Farm milk and developed mild symptoms, including a low fever, which started around the same time the cats got sick. He saw doctors twice, he said. The first time was before the cats had been diagnosed, and he wasn’t tested for bird flu because his symptoms were mild and neither he nor the doctors realized he had been exposed.

After his cats tested positive, he called his doctors back, and they encouraged him to go to the emergency room. Doctors there took blood and ran a battery of tests, but Journell said he didn’t test positive for flu.

Aside from consuming the same products, there may be other, less obvious ways raw pet foods put people at risk, including that many people prepare their pets’ foods in the same space where they prepare their own.

“Those can, of course, contaminate your counters. They can contaminate your utensils, your knives, your cutting boards and so on,” said Dr. Andrea Love, an immunologist and microbiologist who writes the ImmunoLogic newsletter on Substack. “While I would love to believe that everyone has really impeccable kitchen hygiene, we know that that’s simply not the case.”

Pets might spread food around their bowls where kids or shoes might pick it up, or expose people to germs later, when they’re cleaning out a litter box.

At the moment, H5N1 isn’t very good at infecting people because the receptors it uses to enter cells don’t match the receptors that most common in the human nose and throat. But that could change, she noted.

The more contact the virus has with humans, the more it will learn to adapt to us.

“The cats are the canaries in the coal mine,” said Bill Marler, a Seattle attorney who specializes in foodborne illness cases; an attorney in Marler’s firm is representing Journell. “It’s just a matter of time before that raw milk contaminated with bird flu or cat food contaminated with bird flu makes a human sick.”

A growing and risky trend

Grocery stores and pet stores now have whole aisles for frozen and refrigerated pet foods, including raw foods, which are more expensive than dry kibble. The Business Research Company, a market research firm, projects that the raw pet food market will nearly double in size from 2024 to 2028, expanding from $3.7 billion to $6.4 billion.

Raw food typically contains meat and may also have added fiber, vitamins and minerals. Raw milk is also sold as pet food in many states.

Whether pre-made or made at home, vets and infectious disease experts say there are no nutritional advantages to feeding raw diets, and the risks of raw food outweigh any potential benefits, particularly with bird flu circulating.

Raw foods can contain debris, like shards of bone, that may injure pets. Studies have linked some types of raw diets to serious nutritional imbalances, especially when people try to mix their own at home. And tests of raw products show that they are frequently contaminated with harmful viruses and bacteria such as salmonella and E. coli.

“Wild animals don’t live that long in the wild for various reasons. Foodborne disease is presumably one of them,” Weese said.

The idea that raw food is healthier because it is closer to the diets of wild animals isn’t correct, he said.

“The little fluffy dog is sitting on your couch is very much removed from a wolf or a fox in terms of its intestinal tract, intestinal bacteria, its physiology. They aren’t just wild animals that we moved into our house today. They’ve evolved with us and changed with us,” Weese said.

Raw foods may not say so on the package

The FDA says there’s no formal or regulatory definition of “raw” pet food. Although most companies that sell uncooked foods label them “raw” as a selling point, it is not required. Some freeze-dried pet treats are made with raw meat, for example, but aren’t necessarily labeled that way.

Companies often use the term “raw” to indicate that a product has not undergone heat treatment. The foods may undergo other types of treatments designed to reduce pathogens, including high-pressure processing, acidification or irradiation, “however, their effectiveness on viral pathogens such as H5N1 is unknown at this time,” the FDA said in a statement.

The Northwest Naturals frozen turkey that Villain ate had been treated with high-pressure processing, a method the company says kills harmful germs while leaving beneficial microbes intact.

Acfalle said some people may think she was reckless for choosing raw food for her pets, but she had seen raw diets improve the health of dogs she trained by cutting down on digestive problems like diarrhea.

After Villain died, the state tested bags of unopened and opened bags of Northwest Naturals products in Acfalle’s home. Only the opened bag of turkey food was positive for bird flu; the strain of the H5N1 virus in the frozen turkey was a genetic match to the strain that killed Villain.

“We are confident that this cat contracted H5N1 by eating the Northwest Naturals raw and frozen pet food,” Oregon State Veterinarian Dr. Ryan Scholz said in a news release.

The FDA is attempting to trace the source of the contamination in the turkey.

In a Q&A on its website, the company says it doesn’t know how the food became contaminated with H5N1 or why the high-pressure treatment didn’t seem to kill the virus. It said it is continuing to investigate, working closely with state and federal authorities and waiting for more answers in the investigation.

“We remain fully confident in our rigorous quality controls and our ability to ensure that our safe and nutritious food is in our customers’ hands. Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our products and that of our customers’ beloved pets,” the statement said.

There are processes in place to prevent products from sick animals from entering the food supply.

When chickens or turkeys catch bird flu, they typically get very ill quickly and affected farms are placed under quarantine by state regulators and depopulated, or culled, to prevent further spread of the infection.

Quarantine also means no birds or bird products, such as eggs, can leave the facility except for state-approved disposal. This should prevent meat or eggs from infected birds from entering the food supply, according to the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Pet foods are regulated at both the federal and state level, and companies that make them are inspected. These inspections are risk-based, meaning their frequency depends on how risky the ingredients, process and facility are.

Northwest Naturals was last inspected in March, according to the Oregon Department of Agriculture, and had no violations. It was considered low risk.

The FDA has published guidelines for raw food manufacturers that suggest using only ingredients that have been inspected by the USDA and passed for human consumption, but these recommendations are nonbinding and have no legal authority.

Since late last year, Warnings to pet owners have started pop up.

After Villain died in December, Oregon warned pet owners to avoid two lots of Northwest Naturals frozen raw turkey, and the company recalled the food, which was sold through distributors in 12 states as well as British Columbia.

In December, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health issued an animal health alert that several indoor-only cats had died after consumption of raw pet foods and counseling veterinarians to ask owners about feeding raw products to their pets.

Los Angeles County also advised people not to feed their pets another raw brand, Monarch Raw Pet Food, after cats who ate it became ill with bird flu. Samples of the food, which had been sold at local farmers markets, also tested positive for H5 virus.

No recall has been issued for Monarch’s products. In a statement on its website, the company said that it is “committed to the health and safety of pets and their owners” and that “there is currently no credible evidence to suggest that our raw food products are linked to avian influenza or any other health risks.”

After Raw Farm milk and cream were recalled due to bird flu, the farm was quarantined for weeks and California health officials warned consumers against drinking the products or feeding it pets. In a statement on its website, Raw Farm said “there are no illnesses associated with H5N1 in our products, but rather this is a political issue. There are no food safety issues with our products or consumer safety.”

Reckoning with the risks

The news that contaminated raw food led to Villain’s illness was a bitter pill for many pet owners who swear by it. On the company’s Facebook page, fans questioned whether the cat might have gotten sick from being outdoors and somehow those germs got back into the bag of opened food tested by the state.

The Oregon Department of Agriculture said it considered the possibility of cross-contamination early in its investigation. It said the strain of H5N1 that infected Villain was closely related to the strain that’s circulating in cattle, and there aren’t any cattle infections in Oregon, so the agency doesn’t believe cat could have gotten it from its outdoor environment.

Acfalle said that although Villain was sometimes out on a leash, she hadn’t been outside for weeks leading up to her illness because it was too cold.

Both Journell and Acfalle are seeking compensation from the companies that produced their food.

Journell said he has the empty milk jugs from Raw Farm, his receipts showing when he purchased them and the test results from his sick cat, Big Boy, showing that he had bird flu.

His attorney recently sent a letter to Mark McAfee, the founder of Raw Farm, asking him to reimburse Journell for tens of thousands of dollars in vet bills, lost wages and other out-of-pocket expenses.

McAfee said he doesn’t believe that his raw milk could be the source of the cats’ infections since recent studies have shown that the concentration of virus in raw milk drops after several days in the refrigerator. McAfee also said no other pet owners or people have approached him to say they believe they or their pets were sickened by Raw Farm milk.

Journell said he had been unaware of bird flu and had not heard public health warnings related to H5N1 in raw milk until his cats got sick.

“I’m not a scientist, but I have done some research,” Journell said. Based on his reading online, he believed that if it was processed correctly and refrigerated quickly, good bacteria in raw milk would “take care” of any harmful germs.

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

This is a myth, according to the FDA: Raw milk doesn’t rid itself of dangerous pathogens.

Studies have shown that the bird flu virus is present in high concentrations in milk from infected cows and can remain infectious for days.

Journell said he still believes in raw milk, although he’s not drinking it for the time being. “I do believe it has its benefits and is really good for you,” he said.

After Villain died, Acfalle switched her dogs to dried, heat-treated kibble for about a month, but she said they didn’t do well. She said several of them have digestive problems that came back when she switched away from a raw diet.

Acfalle’s dogs are service dogs, and she feels like she can’t expect them to work if they’re not feeling well. She switched them back to raw food, this time from a different brand.

“I still believe in raw feeding,” she said, but it also feels like “Russian roulette” — “possibly risking my dog’s life because some company is not taking the proper precautions.”