What young athletes can learn from the story of Donnie Baseball

Sixteen-year-old Don Mattingly watched on television as the Philadelphia 76ers’ Darryl Dawkins and the Portland Trail Blazers’ Bob Gross clawed for a rebound during Game 2 of the 1977 NBA Finals.

The 6-foot-11, 250-pound Dawkins used his sizeable height and weight advantage to muscle the ball from Gross and fling him to the floor.

Gross bounced up, and Dawkins swung at him. He punched his Philadelphia teammate Doug Collins instead. Then, as Dawkins backpedaled away from the scrum, the Blazers’ Maurice Lucas clocked the center from behind.

“Somebody do something!” broadcaster Brent Musberger yelled.

Everyone on either side, as well as fans, appeared to be involved, until Mattingly saw TV cameras capture the Sixers’ Julius Erving. Dr. J was sitting on the floor, observing everything from afar, not getting involved.

His almost serene manner at that moment, which potentially could have been one of the most tense of his career, stuck with the boy from Evansville, Indiana.

“There’s times when the game’s going fast and things are going bad,” Mattingly said in a 2007 interview. “You gotta be able to keep your sense about you and just stay focused and calm down, get quiet. Instead of having to get all emotional about it, you can stay calm and it’s easier to get through things like that.”

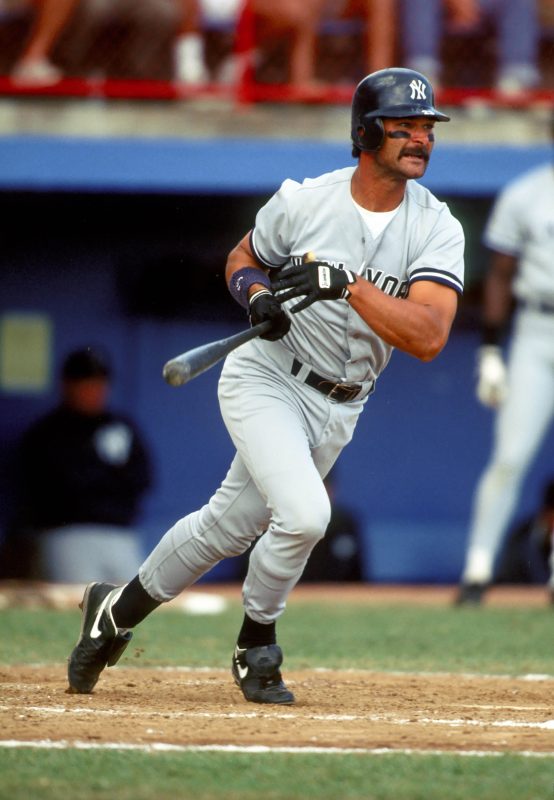

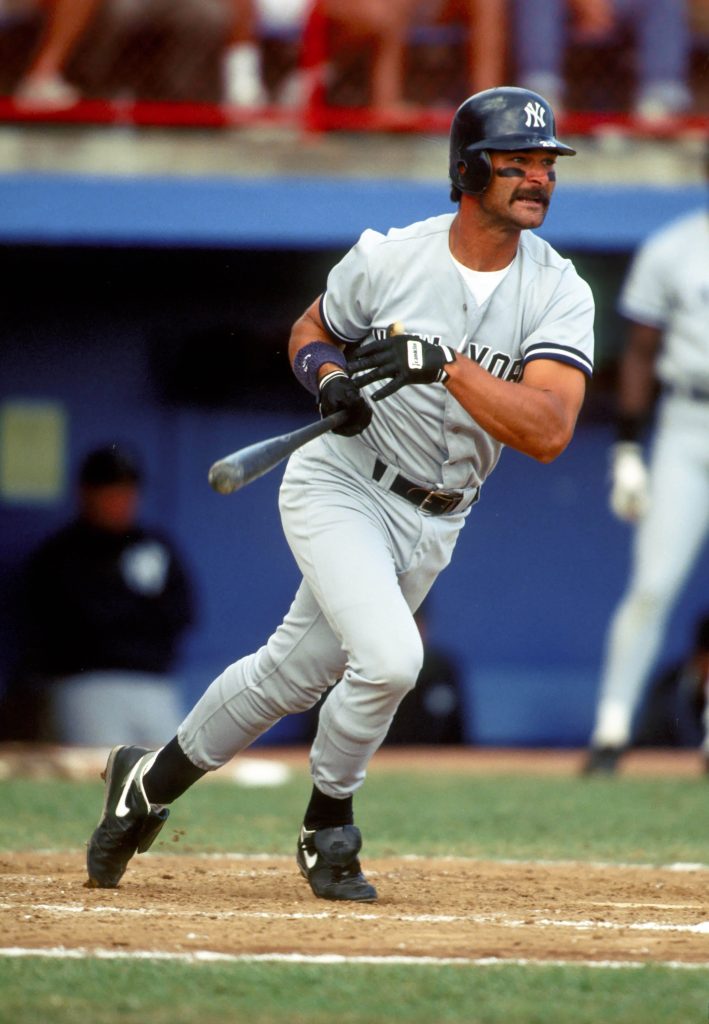

The cool of “Donnie Baseball,” as he became known as the most beloved New York Yankee of a generation and widely respected along his journey that continues in Toronto, has been unmistakable.

You could see it when he first became a professional more than 45 years ago.

“I could tell he was raised right,” recalled Buck Showalter, an early minor league teammate who went on to manage Mattingly with the Yankees. “Many times you’re at the mercy of the mothers and fathers of the world because by the time you get somebody at this level, they’ve pretty much formulated the way they’re gonna treat people.

“You look at their ability, but you also would like to spend a little time with the mom and dad. He was always gonna keep a grip on reality. And I think that’s why New York liked him. It came across every time he opened his mouth.”

Here’s what young athletes can learn from Mattingly, 64, and his patience through the ups and downs of a standout yet gut-wrenching career that has finally landed him in the World Series as Blue Jays bench coach:

As we get better, we don’t have to change what makes us a good person, player or teammate

This year’s World Series began in Toronto, where 30 years ago this month, Mattingly went down to his knee near first base and pounded the turf. The Yankees had just beaten the Blue Jays on the final day of the 1995 regular season, securing the first postseason berth of his 14-year major league career.

“I still remember that like it was yesterday,” David Cone, the former All-Star pitcher and a Yankees teammate of Mattingly that year, would recall decades later, “that emotion on his face, how much that meant to him. …

“The way he prepared, the way he talked to the young players, the way he kind of led by example, he was sort of like the guy everybody looked to in the clubhouse. Every day, you’d look at his locker, watch him get ready for a game, and just the look in his eyes and how professional he was to me was just remarkable.”

Showalter, the Yankees manager from 1992-1995, has observed how jealousy often permeates players pitted against one another in their quest to make the team, or a better team or league. But even in competing with him for time at first base as a player, Showalter could only respect Mattingly. It was impossible to dislike him.

“People trusted talking to him because he just had a pure heart about everything,” Showalter says. “There wasn’t some agenda.

“Donnie didn’t change a bit. He didn’t need to. And I think players fed off that persona. He was just, ‘What’s best for the club?’ Well, our minor league team needs us to play this exhibition game, shut up and go play the game. It was, ‘Yep, we’re getting ready for a championship season. Get on the bus.’ ”

When you watched how his teammates congregated around Mattingly in 1995, you realized the moment wouldn’t have meant anything to him unless he could share it with them.

If you were a Yankees fan in 1995, you still remember the close of that season like it was yesterday. If you were a Yankee, you remember how Mattingly handled its crushing end.

The picture of our lives is larger than what we accomplish on the field

Mattingly made his case as the top player in the game from the mid-to-late 1980s. He appeared at the top of the Elias Sports Bureau’s statistical rankings, while a New York Times player poll in 1986 rated him as the best among them.

That season, he hit .352 and led the American League with 238 hits, while the year before, at 24, he had 145 RBIs and won AL MVP.

There was a rare level of intensity about Mattingly as he worked between games. It didn’t matter if he had three hits the day before off a tough lefty. He’d still be out there the next day with a batting tee and a bucket of balls, by himself with sweat pouring off of him.

It was a scene Butch Wynegar, Mattingly’s Yankees teammate from 1983 to 1986, recalled years later, after Wynegar had become a coach and talent evaluator in the organization.

”You’re hitting .350,’ ‘ Wynegar recalls saying. “He goes, ‘Yeah, but if I can find just one little thing I’m trying to feel’ … Man, what an admiration I had just because of that.”

Mattingly’s back eventually began to wear down from the rigors of his routine. He couldn’t drive the ball with his left-handed swing as explosively by the early 1990s, and his stats suffered.

Finally, around 1995, he found a routine with his back where he could remain relatively healthy, he told Dan Patrick this week.

He batted .321 over the final month of the ’95 season, as the Yankees closed with a 22-6 record, then .417 with a .708 slugging percentage in his five career postseason games.

To Yankees fans, the series was an excruciating five-game loss to the Mariners after winning the first two in New York. To Mattingly, the end was, too, but being in the midst of it all was so much fun: the back-and-forth, the electric playoff atmosphere, the discovery that he belonged in it.

He flew home to New York sad, but walked the aisle of the plane to tell his teammates how appreciative he was.

“He thanked everybody when we all were down in the dumps,” Cone recalled. “He was so gracious and just a class act all the way.

“He waited so long to have that experience and he saw the extra intensity level in the postseason and came through. That shows you what kind of man he is: just that one little taste was enough.”

The players weren’t entirely sure he was about to stop playing but this seemed like the end. It was really just a beginning.

If you love a sport, it really never leaves you

Mattingly missed the start of the next Yankees dynasty, and four World Series titles, to step away and be with his three school-aged sons at his home in Evansville.

He wanted to be present, to have the face-to-face conversations with his kids, about sports or otherwise, we sometimes take for granted.

It was painful to miss out in New York but he says the decision wasn’t hard.

“A lot of people say, ‘Oh, your back …’ ” he told me in 2007. “It was all about my family. I wanted – and not needed – wanted to be there. And I could feel it the year before – when you’re on the road, the kids are getting old enough where they’re in Little League and you’re wanting to be at games and wonder what’s happening and it seems like they weren’t coming to New York as much ’cause they were playing in the summer.

“I look back and don’t have any regrets at all because, again, things you do for your family and kids are years I would never have gotten back.”

After about nine years, his son, Preston, was one of the ones who told him he needed to return to baseball. It’s a part of who he is.

Our playing career can propel us – and other people – forward, long after it ends

I came upon Mattingly in the spring of 2007, in the batting cages at the Yankees’ spring training stadium in Tampa, Florida.

He was in his fourth season on Joe Torre’s coaching staff, and was placing a baseball on a tee for a young player.

“That’s it – that’s the spot,’ Mattingly said as the player connected solidly.

Perhaps you could hear a little bit of the spirit of Bill and Mary Mattingly, Don’s parents, in his voice.

“I always get emotional when I talk about my dad because he just showed up,” Mattingly said, his voice getting choked up during a 2022 MLB Network documentary about his life. “My mom and dad (would) come to every game that I played, and my brothers played, and I don’t ever remember getting criticized by my dad for a game, for a bad play. But nothing on the other side, either. So it was never like, ‘Hey, you were really good today.’

“It was really more just they were there, and I had zero fear of screwing up because I never got criticized. Really, that lack of fear of screwing up allows you to just grow and get better, take chances, not be afraid to make a mistake. It doesn’t work, learn from it and move on.”

Preston, who played in the minor leagues and is now the Philadelphia Phillies general manager, says his dad never pushed him to do anything. He let his son carve his own path.

Torre compared Mattingly at work with players to a doctor with a good bedside manner.

“Sometimes a lot of superstars show up and say, ‘Well here I am,’ ” Torre recalled. “Not necessarily saying it, but you can see it. Donnie was a superstar but he didn’t know it. He’d just come in there and roll up his sleeves and did a lot of work.”

As a coach and parent, we can get better with time

Torre became Dodgers manager in 2008, and Mattingly joined his staff.

“The good thing as a coach is that you almost get better with time,” Mattingly told me that year. “You don’t get worse. As a player, you know your clock’s running, you’re gonna start deteriorating, your skills.

“The more things I deal with in life, the more things I see on the field, the more situations that come up, the more I watch Joe deal with this situation, that situation, the more I learn, the better I am prepared if I ever get a chance to make those kind of decisions and have that influence.”

When Torre retired, Mattingly took over managing the team from 2011 to 2015 and went 446-363 with three National League West titles.

He won NL Manager of the Year with the Marlins in 2020. He did an interview with MLB Network after he won with his fourth son, Louie, who is now 10, sitting on his lap.

As a coach, and a father, it’s all about your players.

“Your true success is guys are having success,” he said in the 2022 documentary as he managed Miami. “You want guys to develop, to be the best players they can be. That’s really what I’m after.”

As he did his round of interviews this week, Mattingly was asked by Patrick what was going through his mind when Toronto trailed Seattle in Game 7 of the ALCS.

“Trust,” he told Patrick.

The Blue Jays, he said, had fun being around one another all season and played well as a team. He knew they could win.

There was a quiet confidence in his words, kind of like what he once saw in Dr. J.

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.