In a city burdened by health hazards of lead, they’re trying to repair school buildings and public trust

As workers set up stations at North Division High School’s cafeteria to test children’s blood for lead, a group of frustrated parents and community activists gathered just outside the main entrance. They carried handmade signs: “Milwaukee–Beer, Cheese, and Lead Poisoning” and “Test All Schools for Lead Now.”

After a child was found to have lead poisoning from peeling lead paint in a local elementary school early this year, the district began closing buildings and temporarily relocating students. It launched a plan to inspect, clean and repaint more than 100 schools by the end of the year, much of it during the summer.

For the crowd gathered outside, it’s not enough.

“This lead crisis is not a new crisis,” said Melody McCurtis, deputy director of a local organization called Metcalfe Park Community Bridges, a grassroots effort to revitalize one of the city’s Northside neighborhoods.

“Milwaukee is full of lead, whether it’s in your homes, whether it’s in your schools, whether it’s in your drinking water,” she said at the news conference.

This year was the first time the city has confirmed that a child was poisoned by lead from a school, but the people of Milwaukee know it’s not the city’s first problem with the potent neurotoxin. The city has fumbled its response before, leaving residents wary of new promises.

Even as the city’s health department and school district work to clean and repaint aging schools, they’re having to rebuild public trust.

And as of last month, they’re doing it without federal help: Lead experts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who had been working with the city were cut during a massive wave of layoffs by the Trump administration. US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy suggested that they would be reinstated, but so far, they have not been.

The unprecedented loss of federal support brought a national spotlight to the crisis in schools. But many families say the latest efforts to clean and repaint old buildings, though well-intentioned, are only a Band-aid. They’re covering up the lead, not getting it out of schools completely.

“We have had crisis after crisis every few years, and we have heard similar kind of things from city leadership throughout that time,” said Derek Beyer, a former teacher with Milwaukee Public Schools, who spoke for the Get the Lead Out Coalition. “It’s been kind of, in my opinion, a game of pass the buck rather than just remove the lead.”

People like him believe that the city’s old infrastructure will continue to cause harm for generations to come.

Lingering threat of lead

Like other major cities in America’s Rust Belt, Milwaukee has long been burdened by lead. Because it’s cheap and easy to bend, it was used to make pipes that carried municipal drinking water. It was added to paint to make it dry faster and last longer and mixed into gasoline to reduce engine knock in cars.

These uses for lead have long been banned, but the threat of its toxicity remains. It can still leach out of pipes, flake off walls and surface in soil. Even small amounts can damage a child’s brain function, affecting their behavior, IQ and self-control.

Each year, about 1,000 children in Milwaukee test positive for lead poisoning, which the CDC defines as at or above 3.5 micrograms per deciliter of lead in the blood. Roughly 15 have to be hospitalized for acute symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation and seizures. About 200 have blood lead levels over 15, which triggers a health department investigation to determine the source.

Most often, they’re poisoned by lead paint in deteriorating homes. In January, for the first time, the health department determined that a child had been poisoned not at home but by peeling paint in the basement of one of the city’s elementary schools.

Many of Milwaukee’s schools had gone without regular painting and maintenance for years: A report submitted to the Wisconsin legislature last year showed that the schools needed more than $250 million in deferred maintenance. Meanwhile, the old lead paint created a fresh hazard as it chalked and flaked off the walls.

Kat Cisar, who has twins in the first grade at the Trowbridge Street School of Great Lakes Studies, found out that the school was abruptly closing and that students would be relocated in an email that came at 7:36 p.m. on a Thursday in March, giving parents and school officials only days to adjust.

As parents dropped off their students at a building 5 miles away from their old school on the next Monday, they had no idea how long they would be displaced or whether a student at their school had been poisoned.

“What happened behind the scenes was a lot of confusion and a lot of uncertainty,” Cisar said the community event on Wednesday. Principals and teachers didn’t have any more information than parents did, she said.

Cisar said parents would like to see better communication from the district, including text alerts if a child at a certain school tests positive for an elevated lead level. They also want school principals to be kept in the loop so they can share timely updates with parents.

Trowbridge was closed for almost two weeks. Other school buildings have been closed for months. Parents say they have no idea how long the hazards existed before action was taken.

Milwaukee Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Brenda Cassellius, who assumed her post in mid-March as the crisis was already unfolding, says schools in the district have been underfunded and individual principals were forced to make impossible choices.

Going forward, Cassellius said, the district will assume the cost of school repairs so they aren’t shouldered by individual schools. So far, the district has spent nearly $2 million to clean and repaint seven schools, and remediation will start on two more this month.

Cassellius estimates that it could cost as much as $20 million from the district’s reserve funds.

That may stave off the crisis, but it won’t be the last of the city’s lead problems.

Toxic housing

Tracy Hampton, a 34-year-old mother of three who was born and raised in Milwaukee, has been trying to keep her kids away from lead for nearly a decade.

When her oldest son, Prince, was a toddler, a test showed that he had a lead level of 27, which prompted his doctor to prescribe iron drops to help reduce the body’s absorption of lead. Hampton was told to wipe down toys and surfaces in their home and make sure he was eating plenty of fruits, vegetables and other healthy foods to counteract the damaging effects of the heavy metal.

But a few months later, a routine blood test showed that he had a blood lead level of 45, more than 11 times higher than the CDC’s threshold for lead poisoning.

“The doctor told me to take him to the hospital immediately, and that’s what I did,” Hampton said, recalling the 2016 ordeal. Dr. Kristine Davison, a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin who has been the family’s doctor for years, confirmed the details of the family’s blood lead levels for this story.

An X-ray at the hospital revealed bright flecks of white in his stomach, a sign that he’d eaten chips of lead-based paint. He ran a high fever, vomited and had a seizure, and doctors worked to flush as much lead as they could from his body.

Around the same time, the city’s health department dropped the ball on lead investigations. An audit of the department’s records in 2018 failed to find any evidence that it had notified some 6,000 families that their children had elevated levels of lead in their blood.

Further investigation showed that the department bungled follow-up care too, failing to investigate the sources of lead exposure for some children. Other instances found that some children’s cases were closed early, before there was evidence that their lead levels had returned to normal.

The failures affected cases going to back to 2015.

The health commissioner at the time was forced to resign. The state and federal governments launched investigations into the health department’s handling of lead poisonings.

It’s not clear whether Hampton’s family was among those that fell through the cracks. She had been spending nights at her mother’s house for help with her active toddler, and she says the Milwaukee Department of Health tested the rental home and found that the windows and floors were loaded with lead.

“It was really old,” Hampton said.

Her mother’s rental home sits on the city’s north side. Between 2018 and 2021, nearly 1 in 5 children who lived in that neighborhood had elevated levels of lead in their blood, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

After Hampton limited the amount of time she spent at her mother’s place and stopped spending the night, Prince’s lead levels began to come down.

In 2022, Hampton moved her family into a different rental home. Prince’s lead levels continued to be elevated, hovering around 6.5. His baby sister, Idanna, also tested over the CDC’s threshold for lead poisoning for the first time.

That house, too, was tested and found to be full of lead paint.

In Milwaukee, 88% of homes were built before 1978, when it was still legal to use lead-based paint. Dr. Mike Totoraitis, the city’s health commissioner, estimates that about 200,000 housing units in the city may still be affected by it, based on their age.

“Unfortunately, the majority of the poisonings that we have in our city are in the poorest housing stock of our city,” he said.

Since their industrial heydays, many Midwest cities have seen their urban populations shrink. Practices like redlining contributed by concentrating Black populations in some of the poorest neighborhoods, which were then spurned by investors. As a result, homes and municipal buildings have aged and deteriorated but were not torn down and replaced.

Rebuilding trust

If there was a silver lining to the scrutiny of Milwaukee’s lax lead response in 2018, it was that the health department’s lead program was completely rebuilt and strengthened.

“That’s frankly how we’re able to respond to this whole crisis at the schools,” said Totoraitis, who joined the department in 2023.

When news of the student poisoning broke this year, the health department set up a dedicated website where it has posted photos of affected schools, inspection reports and letters to parents. It has held regular news briefings and town halls. Totoraitis said it’s also working to create a dashboard so parents can have more insight into the results of student blood tests.

Under pressure from angry parents, the school district parted ways with its facilities manager. The director of the health department’s home environmental health program has been loaned to the district to fill that role as abatement on the buildings continues.

Totoraitis knows that the community remembers — and that shades the department’s assurances to the public now.

“Through that moment in our department’s history to where we are now, we have always leaned into the issues that we’ve seen in our city, in particular with our lead program, and I think that’s helped to rebuild some of the trust that we lost, rightly so, with the community,” Totoraitis said.

At Trowbridge Street School, it’s clear that Room 13 – home to Mr. Koney’s Kindergarten Superheroes – has gotten a recent facelift.

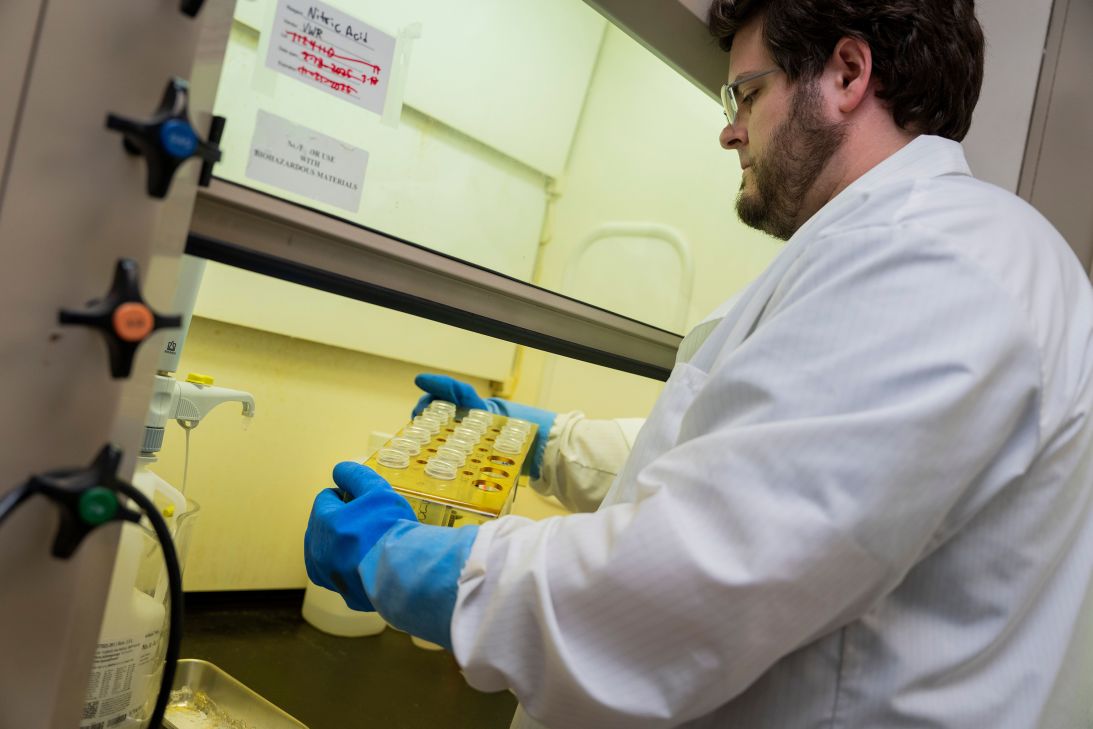

Photos taken during the health department’s inspection showed bookshelves with cracked and peeling paint sitting close to the ground, but the wood is now sanded smooth and painted over. A hallway with hooks for kids’ backpacks now has blotches of fresh paint just a shade lighter than the old blue underneath. Cracks in the walls outside the classroom have been sealed with a white caulk-like substance. The wooden floors of the 129-year-old building gleam with fresh polish.

“It’s almost a hospital-level clean that we’re needing to do to clear the swabs,” Cassellius said, referring to how the health department tests to make sure there’s no lead dust lingering on surfaces.

The department said the lead has been contained at Trowbridge, for now.

But some parents say argue that it doesn’t address faucets where water has tested high for lead or soil around the schools. A soil sample at a playground at Golda Meir School surpassed the state’s action level for lead but not a level set by the US Environmental Protection Agency.

“This is an inadequate response that we’re having at all levels of government here that we’re fighting back, and we’re kind of banding together and figuring out how we can force some of these institutions to do the right thing,” said Kristen Payne, whose son is a third-grader at Golda Meir, the site of the initial poisoning case.

The health department and school district say that drinking water sources in schools are safe. The district has installed filtered water dispensers in schools, and any sinks that have been found to have elevated lead levels are supposed to be labeled as not for drinking.

Totoraitis says that with strained resources, the city has to focus on lead hazards that are known to have poisoned students. For now, that’s the paint.

But he’s asking for money to hire four more people to help him respond to community complaints of chipping paint or other potential hazards before they poison anyone. He could also then inspect school buildings regularly to make sure the district is following its plans to mitigate lead.

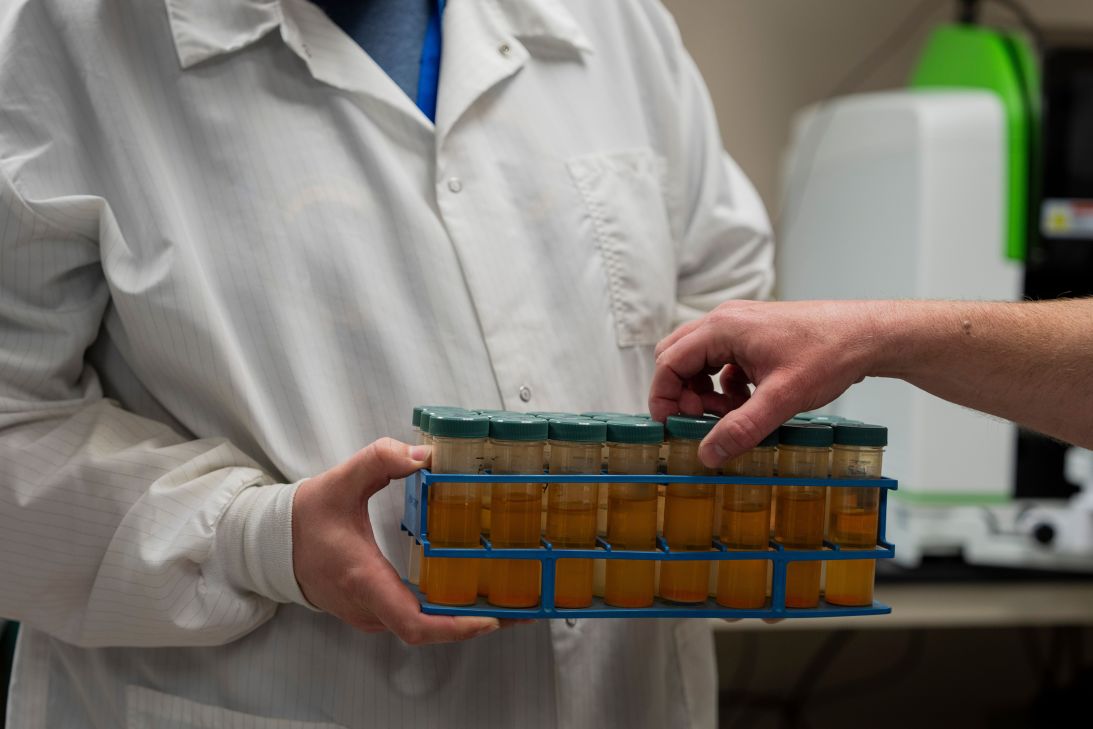

Health officials are encouraging parents of students at affected schools to get them tested for lead. With 68,000 students in the district — most of them beyond the age when they’d get regular lead testing at a pediatrician’s office — the city has been trying create more testing opportunities.

Inside North Division High School on Wednesday, the district hosted a lead testing clinic that would give parents near-instant feedback on whether a child might have a high level of lead in their system.

An earlier clinic tested about 250 kids, but only 22 were tested Wednesday. Of those, two had elevated blood lead levels and will require more testing.

Making schools and homes safer for kids

For now, given the funding they have, the schools and health department say, they can clean up chipped lead paint in homes and schools and seal it under new paint. They can make a building lead-safe but not truly lead-free.

If the repairs are not maintained, the threat will eventually be back.

“It’s a constant cleaning, a constant upkeep, a constant painting. And it is expensive,” Cassellius said.

At some point, trying to maintain Milwaukee’s aging schools – some of which are more than 100 years old – simply won’t be sustainable or safe anymore.

There is some federal help coming for homes in Milwaukee. Totoraitis said the city recently got federal funding to remediate 600, but each project has cost much more than anticipated. In the end, he said, they’ll probably be able to clean up 450 homes.

Helping a single home can have an impact, though.

Prince, who is now 10 and in fourth grade, has trouble reading and writing and needs remedial help in school. He’s also been diagnosed with ADHD. His mother, Tracy Hampton, said doctors have told her that his issues were probably caused by his exposure to lead.

Hampton moved again in 2023, this time into a house that she said was tested and shown to have no lead issues.

This year, for the first time since he was a baby, Prince’s blood lead level has fallen into the normal range again, Hampton said. His sister, who turns 3 next week, is in the normal range, too.

Hampton hopes her story will motivate the city to proactively test more homes and schools for lead and not wait until more children are harmed.

“We need our kids to live, to be smart, to be intelligent, to do what they want to be in life,” she said. “Not to grow up with a disability.”