I don’t have diabetes, but I wore a glucose monitor for six weeks. Here’s what I learned about food (and anxiety)

One day in September, I stood in front of my open refrigerator, ravenous but unable to figure out what I should eat.

I was worried that whatever I chose to eat would cause the new app on my phone to record a spike in my glucose levels that would count against the number I was allowed that day – and I was determined to conquer this algorithm.

I’d just put on a continuous glucose monitor, a device that sticks to your arm and uses a tiny needle to provide near-real-time information about how much sugar is circulating in your blood – not because I have diabetes, the main use for what are called CGMs, but because these devices are starting to be marketed as wellness tools for everybody, and I wanted to see how they work.

Apple? Too sugary. Granola bar? Hello, glucose spike. Cheese – that’s the ticket. A few days of wearing this monitor had taught me that cheese would not cause my glucose to go up.

“Is this thing just inadvertently putting you on the keto diet?” my husband – who’d witnessed a few episodes of hanger while I was trying to figure out how to please my CGM – finally asked.

Pretty much. Avoiding carbohydrates and prioritizing protein and fat, often together, didn’t lead to spikes in glucose that my CGM and app, Lingo from the health company Abbott, would count against me.

But because I wasn’t aiming to switch to a very low-carb, ketogenic diet, I initially struggled to figure out what to eat; in the first week or so of wearing the CGM, my scale read my weight at 3 pounds lower than usual – a blip, I presume, because I was too nervous to eat normally.

CGMs for people who don’t use insulin

This is not, unsurprisingly, how experts say CGMs should be used, whether you have diabetes or not.

Continuous glucose monitors have been revolutionary for people with type 1 diabetes, for whom glucose levels are life and death, providing information about how much insulin they need to inject to keep their blood sugar stable. The alternative is finger-stick testing, pricking fingertips to draw drops of blood to check glucose levels, often multiple times a day.

“CGMs are life-changing for insulin-dependent diabetics,” said Laura Marston, an attorney and advocate for lower insulin prices who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a teenager. Before she got a CGM, she said, she’d go long periods without checking her glucose levels through finger-stick tests, instead adjusting her insulin doses based on how she was feeling, leading to hospitalizations with a dangerous condition known as diabetic ketoacidosis.

Now, Marston said, she knows her glucose level every five minutes with a CGM, and her A1C, another measure of glucose in the blood, is steadily at a much better level – something she attributes both to the CGM and to focusing more on dealing with diabetes and having steadier health insurance.

In that context, CGMs are medical devices, requiring prescriptions and – usually, but not always – receiving coverage through health insurance. CGMs can be covered for people with type 2 diabetes who use insulin, as well.

But this year, Dexcom and Abbott, the two major makers of CGMs, introduced biosensors for people who don’t use insulin, available without a prescription and for about $89 a month out of pocket.

Dexcom’s offering, called Stelo, was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration in March, based on data from a clinical study showing that the device performed similarly to other CGMs.

In an FDA release, Dr. Jeff Shuren, then director of the agency’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said that “CGMs can be a powerful tool to help monitor blood glucose” and that “giving more individuals valuable information about their health, regardless of their access to a doctor or health insurance, is an important step forward in advancing health equity for US patients.”

Abbott’s Lingo was cleared in June and is targeted specifically for “consumers who want to better understand and improve their health and wellness,” the company said in a news release.

The idea is that seeing near-instantaneous feedback to the glucose effects of food, exercise, sleep and stress might give people insights about unique ways their bodies react to different inputs and help them make changes to improve their health.

Putting on the CGM

I was excited to try it. Putting the device on was surprisingly painless, and an hour after the little disc was secured to my arm, I started seeing my glucose levels on the accompanying app on my phone.

“117,” I messaged Dr. Jody Dushay, a physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who works with people with obesity and diabetes and who’d offered to review my CGM findings with me.

The Lingo app told me that was within what it called a “typical healthy glucose range” of 70 to 140 milligrams per deciliter, noting that “occasionally, you may find yourself over 140 mg/dL or under 70 mg/dL, which is expected.”

Dushay had warned me before I put on the CGM that blood sugar could range from the high 50s when fasting to the 150s after eating in a generally healthy young woman. She also emphasized that continuous glucose monitoring shouldn’t be used to diagnose prediabetes or diabetes.

Her caution about how I might react to seeing my data turned out to be warranted.

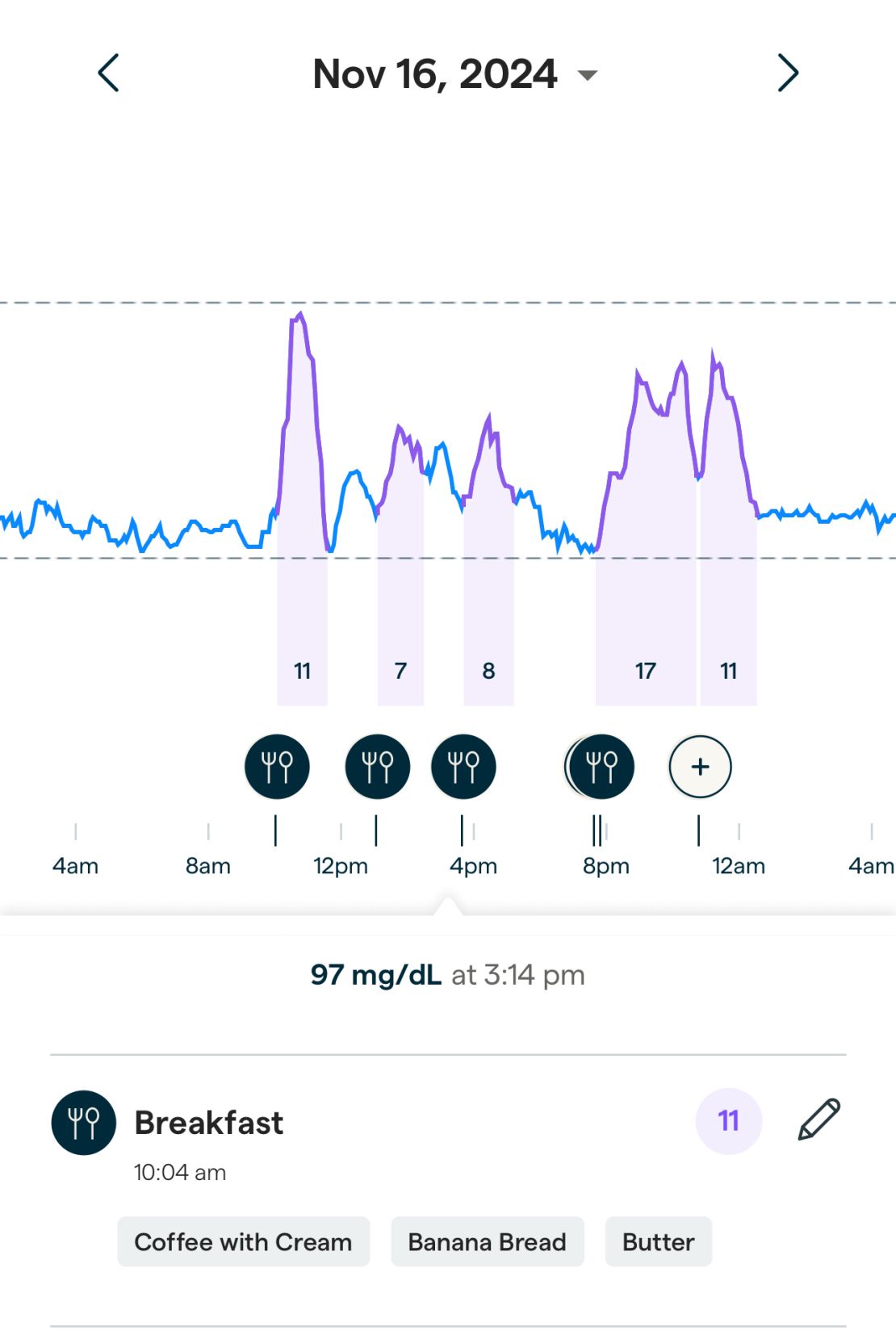

In the first week I wore the monitor, I was glued to the app, watching my glucose rise shortly after eating. The app accumulates metrics that it calls Lingo Counts to try to help users make sense of the data, with a higher number associated with a bigger or longer elevation of glucose.

Although the app gave me an initial target of 60 or under for my daily Lingo Count, I found myself trying to keep it as low as possible, a tendency reinforced by the app’s suggestions to do 20 squats after lunch to “find some balance” as my count was going up. I ended up keeping my count so low initially that the app reset my daily target to 22, which I exceeded frequently once some of my anxiety wore off.

And although the finding that cheese didn’t lead to a glucose spike wasn’t a huge surprise, there were a few other readings that were interesting.

A salad with chopped vegetables and quinoa that I thought was a healthy choice for a quick lunch registered one of my largest Lingo Counts of the week, probably because of the sugar in the peanut dressing. A glass of wine and a slice of pizza, on the other hand, didn’t cause a glucose surge – a happy revelation but not one that I can pretend will lead to better health.

“Your values are all completely normal,” Dushay told me when I sent her screengrabs of my glucose levels. “What look like ‘spikes’ are perfectly fine excursions within the normal range.”

But could those increases, even within a normal range, give me feedback on ways I could feel healthier? Stay full longer? Have more energy? Lower my risk of metabolic disease? Or would I learn only that, as Marston put it, my “pancreas functions as it should”?

‘A lot of strong opinions’

It depends on whom you ask; the scientific community appears to be divided on the value of continuous glucose monitoring for people who don’t have diabetes, a gulf that researchers say is exacerbated by a lack of data.

There are “definitely a lot of strong opinions in the field,” said Dr. Nicole Spartano, an assistant professor at Boston University’s Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine who studies CGM use in non-diabetic people.

Spartano said she conducted a study in which she surveyed clinicians who had expertise on CGMs and asked them to interpret about 20 reports on glucose levels in people without diabetes.

“There’s no consensus about how they view the data,” she said. “Some people think high spikes are bad; some people think they’re meaningless in people without diabetes; some people think, ‘if it’s a prolonged period of a glucose excursion,’” over 180 or so, those people should be screened for diabetes; “other experts will see that and say that person is fine.”

Dr. Robert Lustig, professor emeritus of pediatrics in the Division of Endocrinology at the University of California San Francisco, who’s written several books warning against excess sugar and processed foods, is in the camp that says keeping glucose down is crucial. He argues that continuous glucose monitoring is useful for people without diabetes – if users get the right help interpreting their data.

“Not everybody responds to the same foods as everyone else,” said Lustig, who’s an adviser to a company called Levels that offers continuous glucose monitoring along with an app. “The goal is to keep your glucose down, because when you keep your glucose down, you keep your insulin down, and when you keep your insulin down, then the insulin is not there to drive energy into fat, and it’s not there to cause cell growth, which is at the heart of chronic metabolic disease.”

Lustig acknowledged that people using CGMs could experience the same anxiety I initially felt about the glucose data – but argued that anxiety could be lessened if users receive more help interpreting the information. And Dushay and Spartano emphasized that it would be particularly important for people who have a history of disordered eating or other food anxiety to talk with health-care providers before using a CGM.

“When I eat blueberries, my glucose will not spike at all,” he said. “When she eats blueberries, her glucose will immediately spike.”

With rice, he said, it’s the opposite: His glucose spikes, while Rebecca’s doesn’t. An Indian flatbread he’s been eating since he was a kid also caused a major increase. And sometimes, Gupta said, his glucose can go up to 180 milligrams per deciliter. With a history of diabetes in his family, which he’s discussed on his “Chasing Life” podcast, that’s enough to make him want to avoid those foods.

My own experiment

After four weeks of wearing a CGM – each biosensor device lasts two weeks – I decided to take a break and formulate a better plan before I applied my third and final monitor. I realized that the way I’d approached it the first time around was, as Dushay put it, “an artificial experiment”: I wasn’t using the CGM to get feedback about how I normally eat; I was eating abnormally in immediate response to the CGM.

“Your first biosensor [should be] a look at what you’ve been doing over time, kind of what your body’s been experiencing, even though you didn’t have that peek behind the curtain,” said Pam Nisevich Bede, nutritionist for Abbott’s Lingo business. “And then you’re starting to experiment with a few different food choices, timing of meals, et cetera. And then with your next biosensor, you’re going to be fine-tuning those habits.”

I decided not to look at my glucose levels for the first week of wearing the final monitor, recording my food by hand and entering it into the app at the end of each day. And in the second week, I’d try to make changes.

I also repeated some meals to measure whether my glucose response was consistent, as a National Institutes of Health study found significant variability in CGM readings even in the same person to the same food, according to its author, Dr. Kevin Hall, a senior investigator with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

I’d just baked banana bread with my kids, so I repeated that for breakfast a few times that week and generated a fairly consistent increase in glucose, registering a 10 on my Lingo Count one day and an 11 another. On a third day, exercising afterwards blunted my Lingo Count by a few points.

Even so, my glucose never exceeded about 136 milligrams per deciliter, even at its highest after banana bread. Swapping in Greek yogurt or chia pudding appeared to avoid accumulating Lingo Counts, although I’m not sure I needed a CGM to tell me those might be better choices than banana bread for breakfast.

One thing the CGM did do was nudge me to avoid snacking mindlessly, which may be the kind of small behavioral modification that can make a difference. I didn’t want to have to track every bite of graham cracker I indulged in during my kids’ afternoon snack or to see the resulting increases in glucose on my app.

“I think there’s a place for it in terms of behavioral management,” said Spartano, who’s leading research into whether CGMs can predict the development of diabetes as part of the Framingham Heart Study. “We’re just really early in this research space.”